One of the few films to emerge from Britain’s punk rock movement of the mid-seventies that succinctly expressed the anger and anarchic spirit of the times, Jubilee (1978) is possibly director Derek Jarman’s most accessible film though its irreverent mixture of history, fantasy and agitprop shot, guerilla-style, on the back streets of London is not for everyone. The loosely structured film has a framing device that is set in the year 1578 as Queen Elizabeth I ponders the future of her country. Along with her court magician, Dr. John Dee, and lady-in-waiting, she is transported to contemporary England by the angel Ariel. There she finds a mirror image of herself as Bod, the leader of an outlaw band of deviants, who struggles for dominance in a post-Margaret Thatcher wasteland controlled by the fascist media mogul Borgia Ginz.

One of the few films to emerge from Britain’s punk rock movement of the mid-seventies that succinctly expressed the anger and anarchic spirit of the times, Jubilee (1978) is possibly director Derek Jarman’s most accessible film though its irreverent mixture of history, fantasy and agitprop shot, guerilla-style, on the back streets of London is not for everyone. The loosely structured film has a framing device that is set in the year 1578 as Queen Elizabeth I ponders the future of her country. Along with her court magician, Dr. John Dee, and lady-in-waiting, she is transported to contemporary England by the angel Ariel. There she finds a mirror image of herself as Bod, the leader of an outlaw band of deviants, who struggles for dominance in a post-Margaret Thatcher wasteland controlled by the fascist media mogul Borgia Ginz.

In Jarman’s apocalyptic vision, murder, muggings and widespread lawlessness are the norm, Westminster Cathedral has become a decadent discotheque and Buckingham Palace has been converted into Borgia Ginz’s recording studio. All of it reflects the disillusionment and outrage of an artist reacting against a government in decline, rendered impotent by economic recession, ultra-conservative policies and an ongoing war with the IRA.

It has been said that the punk movement began as an art-school aesthetic expressed through the fashions and clothes created by Malcolm McLaren and Vivienne Westwood in their clothing store in the King’s Road, Chelsea. Jarman became fascinated with the emerging scene and originally wanted to make a super-8 film that captured the milieu around his friend Jordan who worked at the King’s Road store. “Punk…from the start raised questions about sexual codes,” Jarman stated. “It is often argued that punk opened a space which allowed women in – with its debunking of ‘male’ technique and expertise, its critique of rock naturalism, its anti-glamour.”

Howard Malin and James Whaley, who had produced Jarman’s first feature length feature Sebastiane (1976), a gay love story with Latin dialogue based on the final days of the Catholic martyr, St. Sebastian, encouraged Jarman to instead make a movie that capitalized on the burgeoning punk movement. Jarman had, in fact, already filmed the Sex Pistols performing at a 1976 Valentine’s Day party (the footage, one of the earliest surviving records of the band, later appeared in Julien Temple’s The Great Rock ‘n’ Roll Swindle, 1980) and became excited about fashioning a narrative that was fueled by his political and artistic interests and partially inspired by his current interest in Valerie Solanas’s Scum Manifesto, William Burroughs’s The Wild Boys and Erich Fromm’s The Fear of Freedom.  Jarman would later say “With Jubilee the progressive merging of film and my reality was complete. The source of the film was often autobiographical, the locations were the streets and warehouses in which I had lived during the previous ten years. The film was cast from among and made by friends.”

Jarman would later say “With Jubilee the progressive merging of film and my reality was complete. The source of the film was often autobiographical, the locations were the streets and warehouses in which I had lived during the previous ten years. The film was cast from among and made by friends.”  This eclectic group included two key participants from The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975) – the show’s creator, Richard O’Brien, and Little Nell (aka Nell Campbell) who played Columbia; Toyah Willcox, a classically trained actress from the National Theatre; Ian Charleson, who would receive international acclaim for his role as real-life runner Eric Liddell in Chariots of Fire (1981); Jenny Runacre, the versatile art-house star of such films as Pier Paolo Pasolini’s The Canterbury Tales (1972) and Michelangelo Antonioni’s The Passenger (1975); cinematographer Peter Middleton who filmed Sebastiane; costume designer Christopher Hobbs who would go on to work on other Jarman films as well as Todd Haynes’s Velvet Goldmine (1998); composer Brian Eno, a former member of the band Roxy Music who is internationally renowned for his ambient music albums. Jarman also convinced musician Wayne County to play the part of Lounge Lizard and offered small parts to The Slits (as a street gang) and a young unknown, Adam Ant, who had just entered the music scene.

This eclectic group included two key participants from The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975) – the show’s creator, Richard O’Brien, and Little Nell (aka Nell Campbell) who played Columbia; Toyah Willcox, a classically trained actress from the National Theatre; Ian Charleson, who would receive international acclaim for his role as real-life runner Eric Liddell in Chariots of Fire (1981); Jenny Runacre, the versatile art-house star of such films as Pier Paolo Pasolini’s The Canterbury Tales (1972) and Michelangelo Antonioni’s The Passenger (1975); cinematographer Peter Middleton who filmed Sebastiane; costume designer Christopher Hobbs who would go on to work on other Jarman films as well as Todd Haynes’s Velvet Goldmine (1998); composer Brian Eno, a former member of the band Roxy Music who is internationally renowned for his ambient music albums. Jarman also convinced musician Wayne County to play the part of Lounge Lizard and offered small parts to The Slits (as a street gang) and a young unknown, Adam Ant, who had just entered the music scene.

In the biography Derek Jarman, author Tony Peake wrote that “The production was based at Butler’s Wharf. There was some distant location work…but otherwise the film was shot entirely in London, principally around Southwark, Rotherhithe and Victoria Docks. All along the river, the property developers were as active as ever, and throughout 1977 the empty warehouses continued to go up in flames. The apocalyptic desolation of the area, fringed as it was with ‘rotting estates, closed shops and boarded windows,’ mirrored to perfection the desolation Jarman was dissecting, while at the same time allowing him to rescue on celluloid that which the developers were intent on destroying. In this way – and most fittingly, given that punk shared a similar attitude – Jubilee stands as yet another example of the way Jarman liked to rehabilitate what would otherwise be discarded.”  Originally Jarman had hoped that he would finish Jubilee in time to release it during the year of the Queen’s Silver Jubilee but it didn’t actually have its theatrical premiere until February 1978 at London’s Gate 2 cinema. The reaction to the film was decidedly mixed by critics and audiences alike. There were numerous walkouts at the premiere with some people shouting, “This isn’t punk!” at the screen. Others were offended by the film’s numerous depictions of sex and violence while some were simply baffled by Jarman’s off-kilter style with its low-budget aesthetics and artistic pretensions. Vivienne Westwood, the punk fashion designer, proclaimed it “the most boring and therefore most disgusting film I had ever seen.” But there were numerous admirers as well. Variety called Jubilee “one of the most original, bold, and exciting features to have come out of Britain this decade.”

Originally Jarman had hoped that he would finish Jubilee in time to release it during the year of the Queen’s Silver Jubilee but it didn’t actually have its theatrical premiere until February 1978 at London’s Gate 2 cinema. The reaction to the film was decidedly mixed by critics and audiences alike. There were numerous walkouts at the premiere with some people shouting, “This isn’t punk!” at the screen. Others were offended by the film’s numerous depictions of sex and violence while some were simply baffled by Jarman’s off-kilter style with its low-budget aesthetics and artistic pretensions. Vivienne Westwood, the punk fashion designer, proclaimed it “the most boring and therefore most disgusting film I had ever seen.” But there were numerous admirers as well. Variety called Jubilee “one of the most original, bold, and exciting features to have come out of Britain this decade.”  Derek Jarman had the last word on the matter when he wrote in his autobiography, Dancing Ledge: “Afterwards the film turned prophetic. Dr. Dee’s vision came true – the streets burned in Brixton and Toxteth, Adam [Ant] was on Top of the Pops and signed up with Margaret Thatcher to sing at the Falklands Ball. They all sign up in one way or another.”

Derek Jarman had the last word on the matter when he wrote in his autobiography, Dancing Ledge: “Afterwards the film turned prophetic. Dr. Dee’s vision came true – the streets burned in Brixton and Toxteth, Adam [Ant] was on Top of the Pops and signed up with Margaret Thatcher to sing at the Falklands Ball. They all sign up in one way or another.”

BEHIND THE SCENES ON JUBLIEE

Derek Jarman wrote the script for Jubilee quickly and even shot some footage for it before the film budget was even raised.

Producer James Whaley was able to solicit some production money for Jubilee from a former school acquaintance living in Teheran.

At an early stage in production, Jarman wrote that Jubilee was dedicated to “All those who secretly work against the tyranny of Marxists fascists trade unionists maoists capitalists socialists etc…who have conspired together to destroy the diversity and holiness of each life in the name of materialism….For William Blake.”

Before he decided on Jubilee as the film title, Jarman also considered A New Wave Movie, Honi Swar Key Maly Ponce and High Fashion with the letter g in High replaced by a hammer and sickle and the letter h in Fashion replaced by a swastika.

Siouxsie and the Banshees and The Clash were originally going to appear in Jubilee but dropped out after production began because they feared the film was going to exploit the punk movement for commercial gain.

Toyah Willcox was initially given her choice of any role in Jubilee except Amyl Nitrite and selected Mad because she had the most dialogue of any character.

Willcox came from a more conservative background than Jarman and most of the cast and crew and was easily shocked by some of the scenes she was required to do at first.

After first reading the script, Willcox later admitted she was bewildered by it and “I didn’t understand what Derek’s problem was with the Royal Family.” She said to him, “Why do you want to kill them all off?” Eventually she came to understand his point of view but in the early stages of filming she felt that Jubilee was amateurish and that she had gotten mixed up in a bizarre porno-type movie.  Jarman hired Lee Drysdale, who had never worked on a film before, as his production assistant because he was known and well liked among the younger crowd in the East End, many of whom volunteered as extras, providing “local color” in the film. Jarman called Drysdale the “Artful Dodger of Cine-History” because he was such a fervent film buff, often dragging the director to films he would never have seen on his own.

Jarman hired Lee Drysdale, who had never worked on a film before, as his production assistant because he was known and well liked among the younger crowd in the East End, many of whom volunteered as extras, providing “local color” in the film. Jarman called Drysdale the “Artful Dodger of Cine-History” because he was such a fervent film buff, often dragging the director to films he would never have seen on his own.

Lee Drysdale made Jarman angry enough to slap him after the filming of one scene by telling actress Jenny Runacre that she sounded as if she were reading her lines.

Many of the derelict buildings you see in Jubilee were damaged by bombing during World War II and were left standing untouched for years.

For the scenes set in the bowels of Westminster Cathedral, Jarman was able to use the Catacombs club as a substitute set. According to biographer Tony Peake, the scenes were “peopled almost exclusively by friends” and “it lasted all day and involved such quantities of drink and drugs that by the time a wrap was called, some of the participants were so comprehensively unwrapped it would take them a day or two to recover.” Jubilee was an eight week film shoot and was edited at the home of cinematographer Peter Middleton.

Jarman was able to use a fragment of the super-8 film he made with Jordan and Steve Treatment in Jubilee. The scene featured Jordan dancing around a fire while Treatment tossed books into the fire. The original plan was to burn a note and film it, which is a criminal act in England, but that was never captured on film.

Jubilee ran into some censorship trouble prior to the premiere so Jarman had to agree to cut a few seconds from the scene where Crabs and Mad suffocate Happy Days.

JUBILEE FACTS AND TRIVIA

Derek Jarman was an art student who graduated from the Slade School of Art at the University College, London, and became part of a social scene led by sculptor Andrew Logan in the 1970s.

Jarman’s talent as a stage designer led to his first job in the film industry as production designer for Ken Russell’s The Devils (1971). He would also work on Russell’s Savage Messiah (1972) and began shooting his own experimental super-8mm shorts in 1972.

Jarman was also one of the first British film directors to shoot music videos before MTV launched in 1981 and popularized the format. In fact, Jarman filmed three Marianne Faithful videos in 1979 in support of her album – “Broken English,” “Witches’ Song,” “The Ballad of Lucy Jordan.” Among Jarman’s most famous music videos are three featuring The Smiths, prior to Morrissey leaving the group – “The Queen Is Dead,” “Panic,” and “Ask.” He also directed music videos for Throbbing Gristle, Marc Almond and the Pet Shop Boys.

Jordan, the King’s Road shopgirl whose fashion sense expressed the aesthetics of the emerging punk movement, had briefly appeared in Derek Jarman’s Sebastiane (1976) as Mammea Morgana, the famous prostitute who ‘has slept her way from Bath to Rome.’

Helen Wellington-Lloyd, who appears in the first scene of Jubilee accompanied by some huge hunting dogs, was a close friend of Malcolm McLaren and a constant presence in the London punk scene. She plays a major part in The Great Rock ‘n’ Roll Swindle (1980).

John Maybury, an assistant costume designer/set decorator on the film, was a film student who was hired after Jarman met him at a Siouxsie and the Banshees concert. He was assisted in some of his chores by Kenny Morris, the drummer for Siouxsie’s band.

Production assistant Lee Drysdale went on to play a bit part in Empire State [1987] before becoming a screenwriter (Body Contact [1987], Sweet Nothing [1996]) and director (Leather Jackets, [1992]). He lived with Bridget Fonda from 1986-1989 and she also played the female lead in Leather Jackets.

Ian Charleson, who is best known for his role as athlete Eric Liddell in Chariots of Fire (1981), also appeared in Gandhi (1982) and Dario Argento’s Opera (1987). He died of AIDS-related causes in January of 1990.

Jarman would occasionally appear as an actor in the works of others such as Ron Peck’s Nighthawks (1978), one of the first commercial films to emerge from London’s gay underground scene, and David Lewis’s Dead Cat (1989).  Jarman’s film War Requiem (1989) marked the final screen appearance of Laurence Olivier.

Jarman’s film War Requiem (1989) marked the final screen appearance of Laurence Olivier.

By the time Jarman made Blue (1993) he was blind and dying from AIDS-related complications. He would live long enough to complete his final film Glitterbug (1994), a one-hour compilation of super 8 footage of friends and companions set to the music of Brian Eno. He died on February 19, 1994.

The primary instigators of violence in Jubilee are women, an obvious influence of Valerie Solanas who shot and almost killed Andy Warhol. Her notorious SCUM (Society to Cut Up Men) manifesto was read by Jarman prior to filming.

Jarman defended the scenes of violence that occur in Jubilee when he was interviewed by Clive Hodgson for program notes for a National Film Theatre screening of the film: “Those people were posturing violence, they were singing about it, they were writing violent things, but one knows that when it actually happens – and it happens to you – you can have sung about it forever, but it is going to be a completely different thing. This was what I wanted very much to underline in the film, because there was a climate of intellectual violence – ‘Dada’ violence – and that sort of thing can very easily become the forerunner of the real thing.”

In Jubilee, the Amyl Nitrite character (played by Jordan) reveals that her heroine is Myra Hindley. The latter was a famous serial killer who was arrested with her partner Ian Brady for the infamous “Moors Murders” between 1963 and 1965 in which three children and two teenagers were abducted, sexually abused and killed. Her prison mug shot appeared in The Great Rock ‘n’ Roll Swindle and she was portrayed by Samantha Morton in the 2006 TV movie Longford starring Jim Broadbent in the title role.

Amy Nitrite also admits in an opening scene that her favorite song is “Don’t Dream It, Be It” which, of course, was written for The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975) by Jordan’s co-star Richard O’Brien.4

Vivienne Westwood, whose Chelsea store was the mecca of punk fashion, hated Jubilee and created a t-shirt which sported a negative full length critique of the film.

Jubilee was the first of Jarman’s films to reference the Elizabethan period and specifically John Dee, the noted English mathematician, astrologer and consultant to Queen Elizabeth I. The director would return to this period again in his films In the Shadow of the Sun (1980), The Tempest (1979), The Angelic Conversation (1985) and Edward II (1991).

Jubilee features Jarman’s jarring use, in a visual medium, of the written word, a device he would employ more extensively in his later paintings where comments in the form of graffiti such as “Dead Sexy” would be scrawled over abstract colours.

Jubilee, along with Julien Temple’s two films about the Sex Pistols, The Great Rock ‘n’ Roll Swindle (1980) and The Filth and the Fury (2000), Jack Hazan and David Mingay’s Rude Boy (1980), Lech Kowalski’s D.O.A. (1980) and Out of the Blue (1980), directed by and starring Dennis Hopper, are considered the core films that best express the punk movement’s sensibilities and restless spirit.

CRITICAL REACTIONS TO JUBILEE

“…several sequences stoop to juvenile theatrics, and the determined sexual inversion (whereby most women become freakish ‘characters’, and men loose-limbed sex objects) comes to look disconcertingly like a misogynist binge. But in conception the film remains highly original, and it does deliver enough of the goods to sail effortlessly away with the title of Britain’s first official punk movie…” TimeOut

“One of the most original, bold and exciting features to have come out of Britain this decade…could duplicate the cultural impact that Easy Rider [1969] had upon the young generation of approximately 10 years ago.”

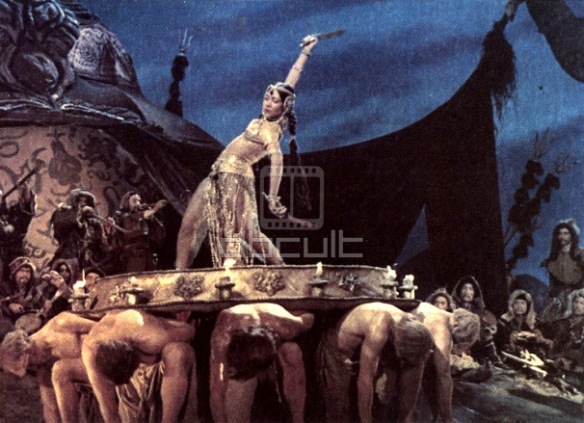

- Variety  “Although Jarman handles the film’s militant women, fetishized violence, and punk rhetoric with an iconic brashness somewhat reminiscent of Frank Tashlin, Jubilee is ultimately too whimsically wordy and fastidiously stylish to be truly effective. Evocative sequences like Jordan’s grotesque striptease production number of “Rule Britannia” are diminished by Jarman’s including such episodes as that in which Jesus Christ is groped at a disco orgy, which compares unfavorably to even the most inept blasphemies of John Waters’s Multiple Maniacs [1970] or Alejandro Jodorowsky’s The Holy Mountain [1973].”

- J. Hoberman & Jonathan Rosenbaum, Midnight Movies

“Although Jarman handles the film’s militant women, fetishized violence, and punk rhetoric with an iconic brashness somewhat reminiscent of Frank Tashlin, Jubilee is ultimately too whimsically wordy and fastidiously stylish to be truly effective. Evocative sequences like Jordan’s grotesque striptease production number of “Rule Britannia” are diminished by Jarman’s including such episodes as that in which Jesus Christ is groped at a disco orgy, which compares unfavorably to even the most inept blasphemies of John Waters’s Multiple Maniacs [1970] or Alejandro Jodorowsky’s The Holy Mountain [1973].”

- J. Hoberman & Jonathan Rosenbaum, Midnight Movies

“Perhaps the suggestion that they could never escape the system is what pissed off punks about the film back in 1978: Jubilee suggests that punk is complicit, even a willing participant, in its own commodification…For all the controversy–and perhaps because of it–Jubilee has remained something of a cult favorite for the last 25 years. Other punk films (like Temple’s The Great Rock ‘n’ Roll Swindle [1980]) have long disappeared. And now we can see that Jarman’s vision of punk’s commodification and England’s future was nothing short of prescient.”

- Todd R. Ramlow, PopMatters  “Jubilee is the most important British film of the late ’70s….And although it strikes parallels with the earlier A Clockwork Orange [1971], Jubilee is impulsive where that film is measured, raw where it is stylized, and unrestrained where Kubrick is exacting. What’s more, in a lethargic and conservative industry that had been defeated by tax and underfunding, Jubilee was the only British film of its time advancing an unabashed social critique…Jubilee, however, seems less like Jarman’s vision than one of a punk cinema collective: it could have feasibly been made by Paul Morrissey on an Andy Warhol sabbatical…Similarly, the film has echoes of John Waters, Russ Meyer, and, fittingly for Jarman (who designed The Devils [1971]), Ken Russell. As such, it is quite a unique experience.”

- Julian Upton, Bright Lights Film Journal

“Jubilee is the most important British film of the late ’70s….And although it strikes parallels with the earlier A Clockwork Orange [1971], Jubilee is impulsive where that film is measured, raw where it is stylized, and unrestrained where Kubrick is exacting. What’s more, in a lethargic and conservative industry that had been defeated by tax and underfunding, Jubilee was the only British film of its time advancing an unabashed social critique…Jubilee, however, seems less like Jarman’s vision than one of a punk cinema collective: it could have feasibly been made by Paul Morrissey on an Andy Warhol sabbatical…Similarly, the film has echoes of John Waters, Russ Meyer, and, fittingly for Jarman (who designed The Devils [1971]), Ken Russell. As such, it is quite a unique experience.”

- Julian Upton, Bright Lights Film Journal

“Its blunt attitude to violence has confused many critics who seem to have missed the point: irony and cynical humor as a means of diagnosing the malaise of contemporary Britain, its paradoxes and puritanism. That there are flaws in the film it’s hard to deny – mainly in terms of its theatrical stage of the story and its attempt to invert gender roles – but it is also difficult to deny the film’s aesthetic innovation which still remains very impressive…Witty, raw and imaginative Jubilee might not provide answers to the burning questions of British society, but it will certainly provide an accurate and often darkly funny description of them.” - Spiros Gangas, Edinburgh University Film Society

“A clever satire on the so-called ‘glorious past’ combined with a bleak look at the future which pulls no punches in its depiction of a once-great country gone horribly wrong…It’s not the most pleasant of viewing, but it’s observant and knowing.” - Channel 4 Film (www.channel4.com)

“Jarman’s sophomore film “Jubilee“, is a Molotov Cocktail of celluloid – a film that practically dares you to watch it…Basically, a giant filmed “F*ck You” to Margaret Thatcher, the royal family and the times in general. Jarman’s visual flair becomes even more apparent. His technique as a filmmaker, garish colors and costumes, unreal settings, another Eno score on a shoestring budget defies logic. It looks and is to this day amazing. The theme of the decline of British society one which he would often revisit, explodes in every frame. In short, the film is punk.” - Thomas Bennett, Film Threat

“The now legendary soundtrack remains one of the film’s biggest selling points, but its chaotic spirit also endeared the film itself to several generations of university students and underground movie fanatics. All others might want to start somewhere else, as this is not the most easily accessible film in the art house canon; the shifts in time and rambling monologues can be daunting to the inexperienced, and those who find Kenneth Anger too heady will no doubt run screaming during the first ten minutes.” - Nathaniel Thompson, Mondo Digital

“Under the direction of Derek Jarman, who also penned the script, this is no self-aggrandizing cash-in in the style of Malcolm McLaren’s Great Rock ‘n’ Roll Swindle, but takes the punk movement seriously, so seriously in fact that it tends to lose the way at times, with a disjointed presentation verging on the incoherent while it mercilessly exposes punk’s flaws. Where it does score is in its gritty imagery, and if the music takes second place to that, then it’s spirited in other ways. The shock value is there, of course, because without the desire to be subversive and controversial, it’s doubtful that anyone would have taken much notice…but now Jubilee, once so sly, modern and of the moment, looks like a antique, an item of nostalgia, and perhaps worst of all, an art movie.” - Graeme Clark, The Spinning Image

“The film is decidedly anarchic, in keeping with late-70s British punk, and depicts a scenario of societal rot, in which the guiding throne is uninvolved. Jubilee precedes the Margaret Thatcher renaissance, and functions as a call-to-question, a statement of disinterest in the threatening use of violence…The film stands as an exemplar of its origin era, both undeniably bold and alienating.” - Rumsey Taylor, Not Coming to a Theatre Near You (www.notcoming.com/)

DIALOGUE AND QUOTES FROM JUBILEE

Angel (Ian Charleson): “I was 15 before I realized I was dead.”

Amyl Nitrite (Jordan): “History still fascinates me…It’s so intangible. You can weave facts anywhere you like. Good guys can swap places with bad guys. You might think Richard III of England was bad but you’d be wrong. What separates Hitler from Napoleon or even Alexander? The size of the destruction or is he nearer to us in time? Was Churchill a hero? Did he alter history for the better?”

Crabs (Nell Campbell): “Leave the guy alone, he’s better than a vibrator and he’s bigger.”

Mad (Toyah Willcox): “You’re a sucker for sex, Crabs. Why don’t you keep up with the times. You’re an antique like this place.”

Crabs: “I just love a man without its uniform.”

Amyl Nitrite: “When I’m not making history, I write it.”

Angel: “You clammy slag! You sat on the KY with your fat arse!”

Borgia Ginz (Jack Birkett): “Without progress life would be unbearable. Progress has taken the place of Heaven….It’s like pornography; better than the real thing.”

Mad: “America’s dead. It’s never been alive!”

Amyl Nitrite: “Our school motto is Faites vos desirs realitie. Make your desires reality. I, myself, prefer the song “Don’t Dream It, Be It”.

Mad: “No one’s gonna help you so help yourselves.”

Amyl Nitrite: “In those days, desires weren’t allowed to become reality. So fantasy was substituted for them – films, books, pictures. They called it ‘art’. But when your desires become reality, you don’t need fantasy any longer, or art.”

Mad: “If your house is ugly, burn it. If the street you live in depresses you, then bulldoze it down. And if the cook can’t cook then you kill her, all right?”

Viv (Linda Spurrier): “Our only hope is to recreate ourselves as artists or anarchists if you like and release the energy for all.”

Bod (Jenny Runacre): “I never liked pearls…or oysters.”

Borgia Ginz: “This is the generation who grew up and forgot to lead their lives.”

Mad: “Sex is for geriatrics. The mindless!

Bod: “The only thing open all eleven in this f*cking county are the police cells.”

Borgia Ginz: “As long as the music’s loud enough, we won’t hear the world falling apart.”

Bod: “Christ! Blue movies for breakfast is more than I can stomach.”

Max (Neil Kennedy): “My idea of a perfect garden is a memorative poppy field.”

* This is a revised version of various articles on JUBLIEE that originally appeared on the Turner Classic Movies website

SOURCES:

Derek Jarman by Tony Peake

Derek Jarman by Rowland Wyner

Derek Jarman: Dreams of England by Michael O’Pray

Midnight Movies by J. Hoberman and Jonathan Rosenbaum

The Criterion Collection DVD liner notes

Other Links of Interest:

http://brightlightsfilm.com/30/jubilee.php

http://www.punk77.co.uk/groups/jordanjubilee.htm

http://dangerousminds.net/comments/one_of_derek_jarmans_very_last_interviews

http://www.400blows.co.uk/inter_swinton.shtml

http://www.jennyrunacre.co.uk/

http://11polaroids.wordpress.com/2014/03/08/derek-jarman-21-photographs/

http://oneplusonejournal.co.uk/2013/03/13/out-of-the-archive-on-derek-jarmans-jubilee-part-1/

http://kaganof.com/kagablog/2012/01/11/63-jubilee-derek-jarman/

http://sensesofcinema.com/2007/great-directors/jarman/